Willie Smits, born in the Netherlands but living in (and citizen of) Indonesea for the past 35 years, works in tropical Indonesia to re-establish not only forests which then increase rainfall by 25% (using only 5,000 acres) but also to re-establish the communities of people needed to make those forests permanent.

Resources to learn more (but also see below):

- Permaculture Voices Talk

- TEDx talk: his work in context of planetary issues and societal collapse

- 3 minute video from weforest.com puts work in larger context

- National Geographic article focusing on role of Sugar Palm and the village hub Tengkawang Factory featured in this video

- In some ways, the work of Shubhendu Sharma resonates: he can create a mature, native forest in 10 years using open source methods based on research by Akira Miyawaki.

Conducted through the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation and the Masarang Foundation, Willie Smits’ work is holistic and integrative, with

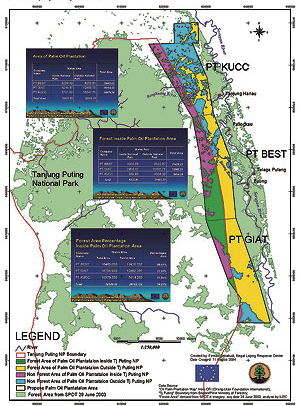

One key to his work is the use of GIS (Geographic Information Systems) methodologies (see this article and this one) to collect a wide-range of data that inform various economic, social and growth models to develop relatively simple recipes that can be replicated and communicated with all types of interested parties (from farmers to investors). As everyone can start to use these tools, it can become obvious that choosing a pipeline (for example) is less sensible than planting a food forest and this can feed back on our political systems.

Smits roots his work in local cultural systems and values. There are three in particular that are most relevant for the agro-forestry component of the work and the social technologies needed to make them effective and sustainable.

(1) The Balanese Subak system of irrigation, a series of tunnels (some more than 3 km) that move water to sustainably grow rice and the wards and society set up to work with water distribution and rights. Tourism has disrupted these systems as land and water is re-distributed toward this “better business”, a redistribution that disproportionately affects the poor.

(2) The Lembo system. The Dayak people have planted successional food forests for hundreds of years. A 1969 regulation established that any land not settled was owned by government. Thus, the Dayak’s 80 year cycle (composed of 8 year sub-cycles) of moving to previously established food forests to allow the current area to heal and restore is no longer allowed.

(3) Mapalos (sp?), a system of cooperative agriculture. 15% higher efficiency is achieved, in part because people sing as they work. This system is also disrupted by modern business practices.

Smits’ planning process is top-down and involves a 25-year cycle, with job creation in every phase. What species can be planted where? Then land-suitability assessment with GIS to identify values of suitability for a particular plant (e.g., Sugar Palm). Using GIS, Smits creates a visual value map with rainfall, soil types, constraints, and minimum requirements for particular species. These maps lead to an understanding of where to implement what recipes in which locations. What about a recipe based on less or more labor? More or less land? The cooperation or lack of cooperation from these 3 farmers? What happens to the plan in an El Niño year? These and other parameters can be tweaked, with different potential recipes then compared to choose the most appropriate. The plan also includes the level of individual fields owned by particular farmers and the recipes for those fields. These recipes include successional time schedules and species interactions. In fact, the overall model includes architectural models of individual trees with some variables calculated based on the the number of leaves to determine mineral, fertilizer, or light needs as well as likely outputs. All of this is combined with market data to find economically suitable recipes given the sustainable resources of each farmer, village, and region.

By outlining a particular area on a map, Smits can quickly see the economics, labor needed, etc. for a given recipe. A business plan follows.

This also works well in conversations with farmers. What is your land? How many hectares does it encompass? What do you normally grow? What is successful and what is not? What price do you normally get for what amount of that fruit? All of these data are entered into a database, along with soil samples, weather station measurements, and satellite imagery and can be viewed on google Earth. Smits shows them the maps piece by piece, assembling a model of hills and valleys where species are most productive. Together, they look at local and regional market demand, come up with best production plan for labor, timing, marketing, and equal profit for each member, for example. These maps can show people different risks — e.g., if we open this field, how does it change water, increase risk of flood, etc. By displaying these data, the benefits of greater cooperation can be seen and even more benefits accrued: by selling via contract timed correctly for boat schedules, for example. Then, each farmer gets instructions about what to plant, how much to plant, and when. The farmer asks, “why?” and the full model can answer that question.

The Sugar Palm (Arenga pinnata) is the king keystone species for Smits’ work and a better option than Palm Oil trees, plantations of which are destroying huge swaths of land throughout Borneo and beyond. The Sugar Palm can be grown in diverse food forests without fertilizers or pesticides, their roots can grow up to 12 meters deep into the ground, and its photosynthetic sugar product can be harvested sustainably every day. All of the energy produced (82 barrels of oil per hectare per year — better than any other existing plant-based competitor) is a huge battery that can be stored in the form of palm sugar and used in many ways, from food to fuel. This plant can yield three times more fuel per acre than any other plant (source). One of the keys to the project’s success in Borneo is using excess heat from a geothermal plant to boil the sugar-saturated sap from the trees, preventing it from fermenting to alcohol and instead resulting in palm sugar. The sugar palm has 65 different products, including the some of the strongest natural fibers in nature — the thinnest one being as strong as steel but at 1/7th of the weight, wood, and fruit.

Out of a billion hectares of appropriate land worldwide, planting 500 million in sugar palms and converting to biofuel could replace all world oil by 2030.

Remote medicine used for people on the land through Skype and sensors for temperature, blood pressure, etc.

![Filename: willies-rocket.jpg Description: [Thumbnail for willies-rocket.jpg]](https://permies.com/t/58088/a/42389/willies-rocket.jpg)

Purchase Willie Smits and Peter Hirst’s talk at Permaculture Voices 1, “Permaculture in a half million-acre forest concession in Indonesia” here.

Rise of the Eco-Warriors Film.

The United States loses about 6,000 acres of forest and open space every year (source) and there are other people trying to help balance people and ecosystem needs to reverse this. For example, the Common Waters Fund (in Delaware) connects landowners to professional foresters in order to improve forest management which, in turn, maintains and improves water quality. Most private forest land is currently owned by people 70 years or older and their primary concern was that the only way to pay the rising cost of healthcare would be to sell their land. At that point, there is a risk that their forests would be cut down by new owners. If that happened to all of this land, it would release more carbon than all of the vehicle traffic in the United States (source). The Pinchot Institute is promoting a program in Vernonia, Oregon, The Forest Health-Human Health Initiative, to trade health care to incentivize good management of forest from landowners and keep their land forested for longer periods of time.

Pingback: Solutions for a Functional Future | One Planet Thriving

Pingback: Life Designers | One Planet Thriving

Pingback: What is Permaculture? | One Planet Thriving