Humans are liars. A great deal of scientific research demonstrates that most people lie, especially under the “right” circumstances. Do a search for Dan Ariely, a Professor of Psychology & Behavioral Economics at Duke University, and you will find many mainstream press articles summarizing his work. This article is about the documentary, (Dis)Honesty: The Truth About Lies, which highlights Dan Ariely and the scientific research on this sub-topic of behavioral economics: lying.

There’s a line between honest and dishonest. How do we behave as humans? What variables cause us to cross that line? These are some of the questions answered by this excellent review of scientific research about lying.

Is lying good or bad?

The movie views lying and dishonesty as unethical and that point of view is a theme throughout the film. They do have a brief discussion on ethical lies or the benefits of lying. One scientist describes how lying and “dreaming big” increases with brain size (e.g., chimps lie to other chimps) and help children develop a more accurate theory of mind. One man tells the story about lying to a woman on an airplane to help reduce her fear about the plane’s response to turbulence. Specifically, he told her he was an engineer and they were perfectly safe: “Better to die with someone telling you a nice lie.” They also highlight a Mom who got her kids into a much better school by claiming residence in a different neighborhood. She was arrested for fraud as a result and later in the movie expresses deep regret — she’s honest Abe now. If you are interested in thoughts about this issue, see this post, “Robin Hood & Other Ethical Cheating“.

Dishonesty

There is a line between honest and dishonest behavior. How far can we cross that line and still consider ourselves good

people? This is what Ariely describes as “the fudge factor”, the grey area we are semi-comfortable operating in. As long as we cheat just a little, we get the benefits for ourselves of cheating, but do not lose our own self-image of being a good person. For example, the speed limit is 55, are you ok driving 60?

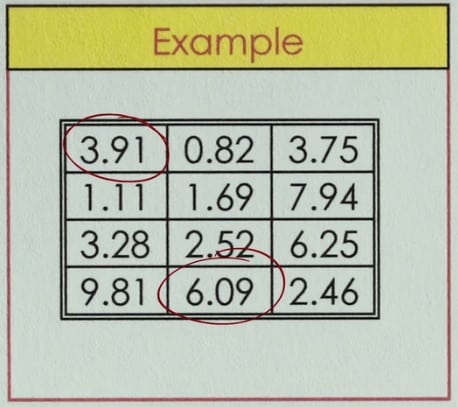

One of their primary experimental paradigms Ariely and his colleagues use is the Matrix Task, a page of 20 math problems, each in the form of a grid like the one pictured. The task is to circle two numbers that

Other results:

- No gender differences.

- Bankers cheat twice as much as politicians. Environment of 2008 is close to combining all of the variables that influence dishonest behavior. The message attributed to this culture of honesty? It is of benefit to their school community and is a winning strategy in life.

- No differences across countries.

What variables change the levels of lying?

- Self-deception. We convince ourselves that good things are true about ourselves, e.g., we’re better drivers than most. Optimism bias seen in 80% of the population. See this post on the dark side of looking at the bright side.

- Social norms. Example 1: If a peer from your college cheats, you are more likely to cheat. If someone from another college cheats, that doesn’t change your rate of cheating. Example 2: The British Government found that if they included in their tax letter the line, “9 out of 10 people pay their taxes on time”, revenue collection increased from 30 to 35%. Example 3: People cheat more if they team up with someone cheating.

- Creativity and dishonesty can go together. If you prime creativity (e.g., by looking at art), people are better at justifying cheating.

- Distance from money. People cheat more if they get plastic tokens they turn into money at another table than if they directly get money from their lie.

- Lying for the benefit of others. Example 1: Mom lies that her children live in a neighborhood with a better school district. Example 2: If you lie for a charity, a lie detector will not respond because their is no conflict in you and thus no arousal

- Conflicts of interest. Example: Referee making money from betting (through a third party) on the games he is refereeing.

Honesty is important

Social trust is more important than job skills for economic growth

How do we get people to behave better?

If we don’t, we’ll get more disasters like the 2008 financial crisis. The Isha Vidya school in India is profiled: everyone is honest, including at their “honesty shops” where students pick out and pay for supplies on their own without supervision.

You can prime morality and that reduces cheating on the matrix task. e.g., After priming the 10 commandments (regardless of the student’s religion and how many they remembered) or swearing on the Bible, or signing on an honor code (whether or not the school actually has an honor code), nobody cheats on the matrix task. A 1-week course in morality, has no effect — it is the priming of the moment that is more important.

Pingback: Robin Hood & Other Ethical Cheating | One Planet Thriving