“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.” – Aldo Leopold, Round River, Oxford University Press, New York, 1993, pg. 165.

A generalized version of this statement apples to anyone who understands, lives, or expresses an unpleasant perspective (whether true or false) about any topic. Note the word “unpleasant” rather than “negative”. This is because there can be unpleasant observations that are very positive to know about (e.g., the presence of a rattle snake so we can avoid it) and pleasant delusions that are very negative for our lives (e.g., ignoring the presence of a rattle snake; For more, see this article and this one). People who do have the ability to see unpleasantness without running away will see a world of wounds that others do not see and they will often feel alone. These people are, in a sense, living on the edge, an edge defined by social isolation.

Consider someone who states something that we don’t agree with politically. Or, consider the fact that some of us are uncomfortable interacting with people who are chronically ill or disabled, perhaps because they remind us of unpleasant truths (e.g., our own vulnerability or mortality). Consider what happens to whistle blowers and how important they have been as a check on undemocratic/non-transparent use of power (e.g., Daniel Ellsberg). Consider poverty, climate change, and a list of other realities that represent serious current problems that we don’t seem to address.

As the statement from Leopold suggests, anyone understanding or expressing or living an unpleasant truth will often be met with a variety of avoidance reactions (see this article for more) from others and may feel alone, outcast, and marginalized as a result.

What makes a truth unpleasant is that it’s a truth (or a perspective) that causes unpleasant emotion for others, probably because it threatens our current way of coping emotionally in an unpredictable world. Carl Jung wrote, “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light but by making the darkness conscious. This procedure, however, is disagreeable and therefore not very popular.” (The Philosophical Tree, 1945. In CW 13: Alchemical Studies, p. 335)

No wonder we decide to keep things “positive”, a word that is often just a euphemism for pleasant (see this article). But do we really want to interact with each other pretending to be someone else and hiding who we are? Do we really think things are going to go well for ourselves and our planet if we hide our version of the truth?

At this point, some people would point out that authenticity can resonate with people. One might remember T.S. Eliot’s statement, “that which is most personal is most universal.”

But how do people live in authenticity when that integrity involves the seeing and expressing of unpleasant truth given the reactions of other people? How do things turn out for those folks?

Consider hip hop artist Lauryn Hill: “See fantasy is what people want, but reality is what they need. And I just retired from the fantasy part.” In other words, she decided to be the doctor in the village and talk about the “marks of death” she saw. Partly as a result, she experienced racisim and other avoidance reactions from people and withdrew from public life.

Consider Carlton Pearson, an evangelical Christian preacher who started to talk about inclusion to his congregation and was subsequently disincluded from that church community (see the documentary, “Come Sunday”).

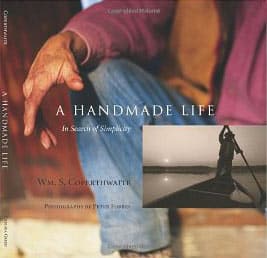

Or, Bill Coperthwaite who wanted to “do less with less” and championed non-violent, democratic design for the love of people, who yearned for community, but lived mostly alone.

What of Martin Luther King, Jr., Gandhi, or Jesus?

We might hypothesize that the more counter-cultural and unpopular the unpleasant truth, the more rejected the speaker will be (using whatever reason is most convenient). Human history is full of examples of people being otherized (“you are not me, you are the other”) and treated in truly horrible ways because they were different in some way, whether it be color, gender, sexual orientation, religion… Unfortunately, the list of ways to otherize people is nearly infinite. How we are seen by others can be a form of hell, one reason Sartre famously wrote in his play, No Exit, that “Hell is other people!”

We can imagine a kind of order of popularity that comes from the two dimensions of authenticity and conformity (from most to least popular):

- authentic conformity: someone speaks an authentic truth that we want to hear

- inauthentic conformity: someone who flatters and says the right things socially

- authentic non-comformity: someone speaking their truth when that truth is unpleasant and not popular

- inauthentic non-comformity: like the inauthentic conformist, this person values other’s opinions, but this time rebelling against them

The most popular strategy outlined by Leopold for authentic non-conformity is an avoidance strategy: armoring our hearts and pretending the wounds don’t exist. In other words, start ignoring our truth and conform (or at least be quiet).

If we are not enamoured of the idea of shutting down and being silent about our truth, the other strategy Leopold identifies is being an authentic and helpful non-comformist who sees clarity in a deluded community that doesn’t want to wake up. That doesn’t sound so good either. Consider Michael Bennett, a champion NFL player, who observes: “But your money is tied to your silence. Your money is tied to walking the line.” (p. 50, Things that Make White People Uncomfortable) or “If you’re not doing what people think you should be doing…you are seen as a misfit.” (p. 115) or “I think we get attacked for standing up for others precisely because doing so opens up an avenue for change, and change threatens the status quo of those in positions of power. And that can bring you all kinds of unwanted attention” (p. 170).

But if we did decide to engage with this option, what Leopold doesn’t offer in his statement is how to be a skillful doctor. How do we help people who do not want the help or perhaps feel violated when someone even points out that help is needed? After studying pyschology as both a scientist and therapist, I would offer the following simple possibility: (1) communicate unpleasant truth as skillfully as possible (see this article and this one), (2) if doing so is important to you and/or likely to help others, and (3) sustain yourself in these difficult activities by seeking out and enjoying the company of people who are supportive.

Given the many dysfunctional aspects of status quo (e.g., climate change, war for oil, inadequate healthcare, and so on), finding ways to skillfully speak truth in the world has never been more important, but it does involve living on the edge. In his book, Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates tell his son, “…you are called to struggle, not because it assures you victory but because it assures you an honorable and sane life” (p. 96). About being in the world, Coates also says: “…my wish for you is that you feel no need to constrict yourself to make other people comfortable. None of that can change the math anyway.” (p. 107-8).

Living on the edge is lonely (“we live alone in a world of wounds”) and the process of interacting in such a world with educated eyes is difficult. Given the essential importance of connection for human beings, it is important to find our people. Coats says, “I now know that within this edict [“They must all take their beating together”] lay the key to all living…whether you fought or ran, you did it together” (p. 69).

In his poem, I would I Were a Careless Child, Byron speaks about the importance of finding his midnight crew.

Though gay companions, o’er the bowl

Dispel awhile the sense of ill;

Though Pleasure stirs the maddening soul,

The heart—the heart—is lonely still.

Light and easy friends socializing over the punch bowl are not satisfying for Byron who longs to “fly the midnight crew” roaming the “dusky wild” and the “mountain’s craggy side.”

It is perhaps significant that edges in our environment — between the forest and a meadow, the border where land meets water — are the most productive, life-giving ecosystems on the planet. Just as the edge is vital for life on Earth, perhaps the perspective of humans on the edges can help us learn to thrive on our planet.